One Water: An interdisciplinary approach to client challenges

By Katherine Amidon (Posted Feb. 22, 2019):

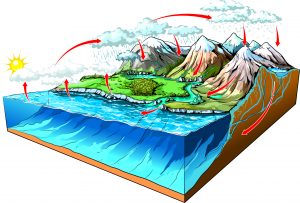

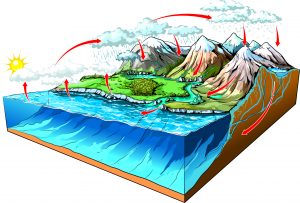

The water cycle — that continuous movement of water throughout the environment — hasn’t always received the attention it deserves. Today, there are encouraging signs the water cycle and related environmental concerns are taking prominence in our curricula and our awareness.

As a child, I was intrigued with the water cycle. It was that continuous movement of water throughout the environment. It was simple and complex and perpetual. Our lives and the lives of all creatures depended on it. That’s how a second-grader thinks — in extremes. Unfortunately, that initial wonderment wasn’t nurtured, and it was short-lived.

Now, as an environmental planner, I am disappointed that this basic concept did not have a bigger presence in my K-12 experience. Topics like acid rain, stormwater runoff, permitting requirements, and pollution control were not big parts of the curriculum. But to my joy, attitudes and awareness are changing. Throughout the United States, we are doing a better job of educating young minds about the negative effects human activities can have on our water. We’re also doing a better job of educating older minds. Clean water initiatives are taking center stage locally, statewide, and nationally. Environmental issues, including the perilous condition of our global water supply, are gaining an increasing foothold in K-12 curricula, adult education, and community outreach. The water cycle, finally, is becoming a continuous part of education, and the rewards are becoming cyclical.

For example, Section 319 Grant recipients in South Carolina commonly cite education, including that of landowners, as a critical driver of their accomplishments. Public outreach has become an education-based strategy within itself, and that’s by design. MS4 permits, which address stormwater discharges, require public participation/involvement and have led to innovative teaching programs. The City of Greenville, which holds an SMS4 permit, provides a credit to local schools on their stormwater utility fee if they partner with the city and teach their students about stormwater. This type of partnership allows funding to stay within the school system and encourages increased understanding. Students then tell their parents what they learned, passing along key information. The Reedy River Water Quality Group Public Outreach Committee, of which I am a member, has launched creative campaigns, including Do It On Your Lawn and Go Au Naturale. These campaigns are fun in tone but serious in purpose. They emphasize that even the most basic activities can affect local and regional water quality.

Bedrocks of recent progress

An examination of recent progress really must look back to the 1970s when the Clean Water Act (passed in 1972; amended in 1977 and 1987) and the Safe Drinking Water Act (passed in 1974; amended in 1986 and 1996) laid important foundations. Myriad improvements have followed, including increased regulation of point source pollution. We have taken big strides, but there’s a long way to go especially with nonpoint source pollution. We must educate better; we must plan more effectively; we must protect our water more diligently.

Here at SynTerra, we try to leverage the expertise of diverse backgrounds to solve environmental challenges. We incorporate proven practices and approaches, and we look to big picture strategies, like the American Planning Association’s (APA) One Water policy. That policy focuses on five main categories:

- Human use (both potable and non-potable)

- Stormwater management and flooding

- Ecological and natural resources

- Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM)

- APA-specified actions

Water-focused planning is critical as our urban areas grow, the effects of climate change mount, aging infrastructure challenges become more prominent, and technological advances transform the water industry as a whole. Collaboration among water engineers, water managers, landscape architects, planners, and community members is imperative as we address water quality and quantity concerns. As a planner, I advocate and follow a holistic approach to water planning. Planners must think beyond the four corners of the project and consider the impact as a whole. That’s the essence of One Water; it’s a reminder of the basic water cycle we all learned about, even if it was long ago.

As we know all too well, but are quick to forget, nature does not observe our manmade boundaries. Water moves beyond our personal property, the city limit, and the county line … and we should plan for that.